Meira Yagid- Haimovici, Curator

It's The Light

Ayala Serfaty: Soma

Light Installation, 2008

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

'Jōshū asked [his master] Nansen, “The Way – what is it?”

Nansen said, “It is everyday mind.”

Jōshū said, “One should then aim at this, shouldn’t one?”

Nansen said, “The moment you aim at anything, you have already missed it.”

Jōshū said, “If I do not aim at it, how can I know the Way?”

Nansen said, “The Way has nothing to do with ‘knowing’ or ‘not knowing’. Knowing is perceiving but blindly. Not knowing is just blankness. If you have already reached the un-aimed-at Way, it is like space: absolutely clear void. You cannot force it one way or the other.”

At that instant Jōshū was awakened to the profound meaning. His mind was like the bright full moon.1 '

'Where does the work belong? The work belongs, as work, uniquely within the realm that is opened up by itself.'

Martin Heidegger2

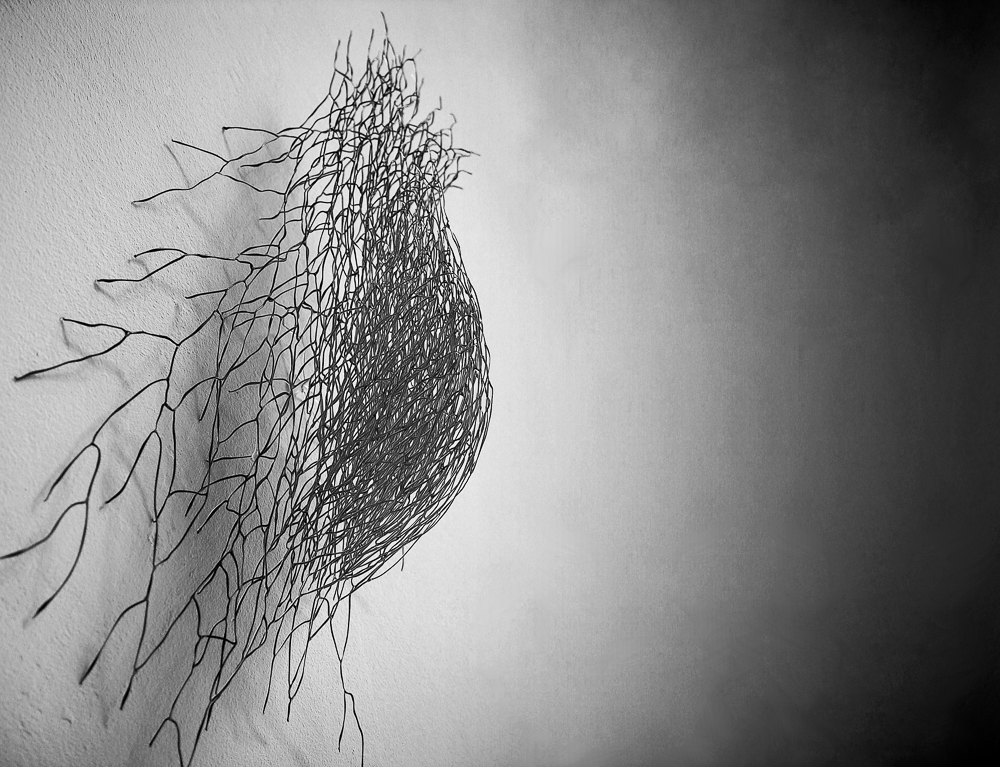

Six years ago, in 2002, Ayala Serfaty saw on the wall of the Ceramics Department of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design something that was to generate a turning point in her work: a fragile web of glass filaments that unraveled her thinking. The process it sparked, which gave birth to the installation Soma, might be described as the transformation of calligraphy into three-dimensions, a manual, labor-intensive process in which fine glass filaments are interlaced to create spatial structures. A membrane-like overlay of clear polymer allows the changing hues of the filaments to shine through, revealing something of the glass maze within.

As the work (or evolving work) on Soma took shape, it broke through into the wider metaphorical space, moving toward abstraction and reduction. The concrete images disintegrated and began to defy clear representations of nature. Behavioral nuances burst from the form into space, intensifying the fundamental qualities of the object. Matter became thought.

'How do we choose our specific material, our means of communication? “Accidentally.” Something speaks to us, a sound, a touch, hardness or softness; it catches us and asks us to be formed. We are finding our language, and as we go along we learn to obey their rules and their limits. We have to obey, and adjust to those demands. Ideas flow from it to us and though we feel to be the creator we are involved in a dialogue with our medium. The more subtly we are tuned to our medium, the more inventive our actions will become. Not listening to it ends in failure…What I am trying to get across is that material is a means of communication. That listening to it, not dominating it, makes us truly active, that is, to be active, be passive. The finer tuned we are to it, the closer we come to art.'

Anni Albers3

The medium is the language; the webs are the narrative. The light shining through the skin of the installation is the body in which form and content merge inseparably. It is a further evolution of the light that shone through the leaves Serfaty painted as a student in London in 1985-87, when she encountered the work of Eva Hesse, the use of the medium as a conduit, the sensual treatment of industrial materials (latex and fiberglass), the physical dimension of the work, the sense of doubt, and the essence of “unravelings.”

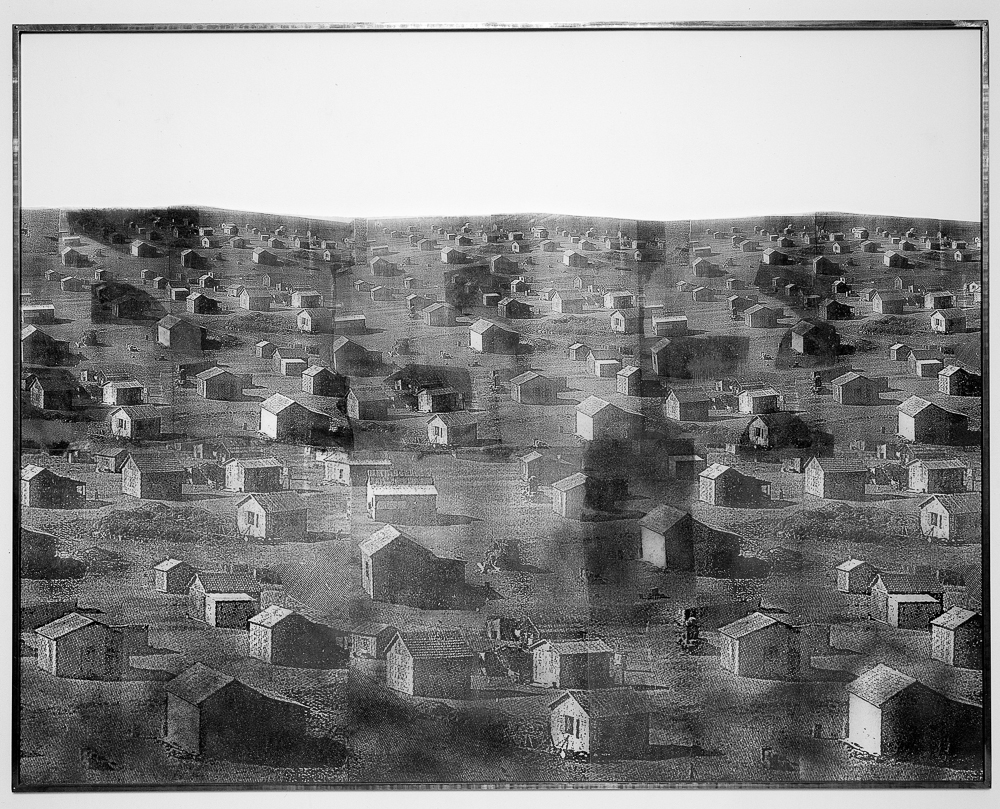

Eva Hesse was among the first artists in the 1960s to deliberately turn to unconventional materials as part of a cultural attempt to extend the borders of art. Her work is characterized by a delicate balance between the planned and the random, between conscious knowledge and the dimensions of surprise and revelation. More than twenty years later, this essential quality found its way into the material state of the objects created by Serfaty. Indications of this development can already be seen in the artist’s early works: pictures painted in dust molecules; paintings on wax; plastic bags; topographies of the Judean Desert engraved onto aluminum surfaces; an installation of glass hammers. A whirl of family history telling of settlement in Israel and two families partially lost in the Holocaust eddies through the atmosphere of light.

'Mist covers the whole city of Kyoto and the booksellers take their books in off the sidewalks and into the shops because the passersby are walking blindly and knocking the books of philosophy and economics and history onto the ground.'

Yoel Hoffmann4

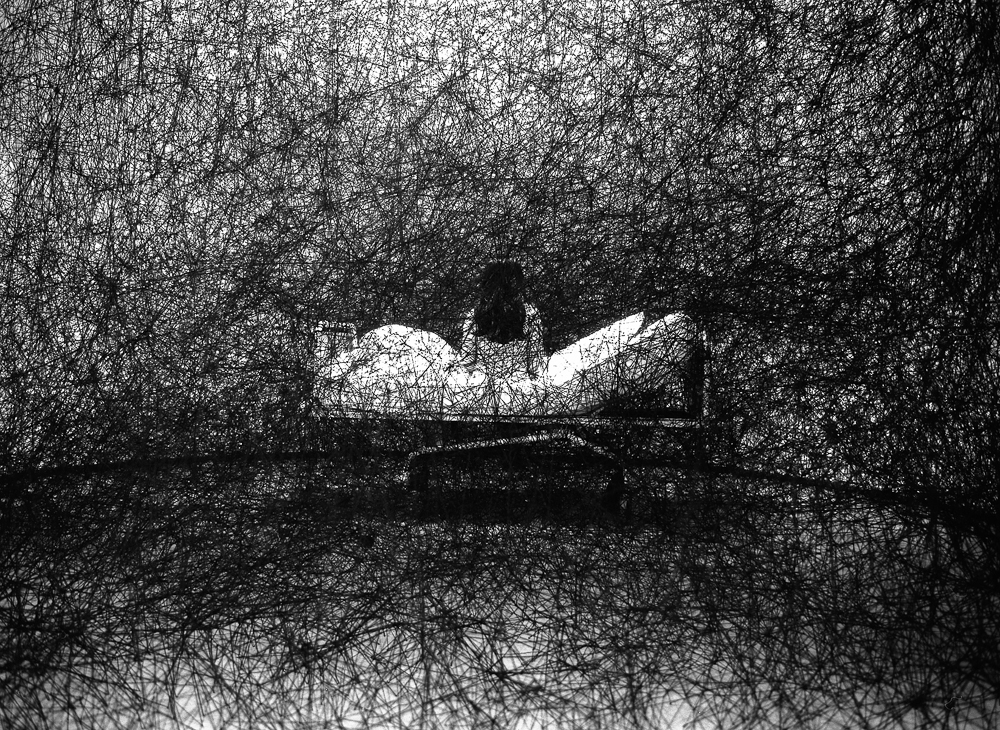

The lengthy process of the creation of Soma – a breathing metaphorical structure of a body within a body – spreads like a hazy topography throbbing over a surface of granulated glass wrapped in felt. The name Eva Hesse gave her work – Expanded Expansion – might also be applied to the large metaphorical space of Soma. Here the quivering limbs operate as an interface of 24 units tangentially linked in a rhizomorphous construction, each breathing into and through the others while breathing autonomously as well.

Soma must be read openly, progressively: the glass filaments are woven into a crystal- like structure and wrapped in polymer threads to create a surface that resembles a brittle, fragile cocoon. Its physical identity took shape in a slow, cumulative process. Yet the moment it was turned into a cocoon by means of the polymeric spray,5 the exacting effort of its creation was obscured.

'The clouds and atmosphere of the real landscape are not the same throughout the four seasons. In spring they are bright and harmonious; in summer dense and brooding; in autumn thin and scattered; in winter dark and gloomy. When an artist succeeds in reproducing the general tone and not a group of disjointed forms, then clouds and atmosphere seem to come to life.'

Kuo Hsi6

Like a journey or a process, Soma went through several stages. It began with the imitation of nature in pictorial works which then fluctuated (in a dialectic phase) between expressions of the consciousness and images of natural phenomena, as if they were ornaments in dissolve. Living nature had become inanimate, a descriptive narrative which gradually emerged from reflections on a Japanese Zen garden. But like a fish in an aquarium confined by the walls and floors of the tank and prevented from swimming out far and deep, as it progressed, Soma yearned to free itself of time and captivity. It now began to take shape not as intersecting lines, but as a surge into the cycle of life, into nature throbbing with life forms. The thick “vaporous” monochrome of Soma is an embodiment of this passion, the urge to reach out to matter and color, to the color that derives from the matter.

Nature, with all its forms, structures, and organizing principles - the sea and the land, fauna and flora- has always been a source of inspiration for artists and designers. After generations of formalism, this connection has become even stronger in recent years. Nature’s role in design reached its height in three periods: in the Art Nouveau of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in works produced by artists such as Émile Gallé, Victor Horta, and Antoni Gaudi, where it served an ornamental function drawn from the dynamics of plant-life; from the 1930s to the late 1960s, when the interaction between nature and design was aimed at achieving an organic harmony through a purist use of natural materials; and in the last decade in a design language grounded in a new interpretative use of nature. This language does not mimic nature in the ornamental sense, but rather utilizes it and its complex structures as an endless source of inspiration

for the creation of new forms.7

'Understanding the object and understanding the personality – they are to be seen as opposite poles: the pure inanimate object has only an external manifestation, which exists solely for the other and can be fully and thoroughly revealed by the unilateral act of this other (the person who is familiar with the object) – this object – devoid of any internal existence of its own, which is not detached and is not consumed, can be the object of practical interest alone. The other pole

is contemplation of God in the presence of God: dialogue, questioning, prayer. The personality must open freely. It has an internal core that can not be used up, consumed. A distance is invariably preserved, in respect to which only the absolute lack of object interest is possible. When it opens itself for the other, it remains at all times for itself as well.'

Mikhail Bakhtin8

In terms of the history of Israeli design, Ayala Serfaty has always belonged to another space. She is an artist “without a country,” loyal to herself, outside the local design scene (which is reductive in its use of media and reflective in its creative process, working mainly with ready-made and improvisation). Over the course of two decades, Serfaty constructed her own language, which might be described as the material incarnation of Bacchanalian physical theater, a performance staged in a highly expressive manner with an intensely passionate freedom. Her subjects are undeniably performative. The presence of the female body in her works is also alien to the discourse of local, patriarchal design. Yet the sexuality of the female body is deeply imprinted on the silk works with which she was identified for many years. These soothing, pleasurable creations are suffused with the joy of life.

'Write yourself. Your body must be heard. Only then will the immense resources of the unconscious spring forth...At last, boundless feminine imagination will be revealed.'

Hélène Cixous9

“I do not sculpt birds, but flight,” said Brancusi.10 Soma holds the viewer’s gaze. In Serfaty’s light installation, the romantic image of grand “nature” has evolved, going through phases of transformation and refinement until it appears today as an enigmatic metaphor more than a source of attraction and temptation. The work, composed of surfaces that trap or merge with one another, operates on the aesthetic level in an attempt to experience movement toward the sublime, to rise above the mundane, above the medium itself. At the point where Serfaty succeeds in unraveling the seams, that which has been lying dormant for years begins to emerge.

Soma captures the viewer’s senses on two levels: on the level of the immediate sensual experience and on the reflective level, as discourse on beauty and the varied and contradictory tendencies it arouses. The glass structure with its membrane-like overlay resembles a rhizome – a horizontal root-like stem spreading seemingly at random over the ground. It makes no difference from which side we enter, as no side is more important than the others. It is only the principle of the myriad entry points, or the hesitative pauses, that thwarts interpretation of the work as an object inviting us to experience it for ourselves. Soma oscillates with the tension between the desire to unravel and the longing to become totally immersed in the infinite possibilities, until one is no longer able to determine where it all began.

Notes

- Yoel Hoffman, Radical Zen: The Sayings of Yoshu (Berkeley, CA: Autumn Press, 1978), p. 13.

- Cited in Timothy Clark, Martin Heidegger (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 62.

- Cited in Catherine de Zegher (Ed.), Eva Hesse: Drawing (New York: The Drawing Center & Yale University Press, 2005), p. 36.

- Yoel Hoffmann, Curriculum Vitae (Jerusalem: Keter, 2005), passage no. 53.

- The creation of light fixtures in the shape of a plant bulb or cocoon became possible in the 1950s and

- ‘60s through the use of a new self-skinning spray developed in the USA during the Second World War to coat ships and protect from dust, rust, and mildew. The American architect and designer George Nelson (1908-1986), also known as an insightful thinker, produced the series “Bubble Lamps” over the course of thirty years, starting in 1952. In 1960, the lighting company Flos displayed the Taraxacum series of hanging cocoon-like lamps designed by the Castiglione brothers. Ayala Serfaty saw an exhibition of these lamps at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1998.

- Kuo Hsi, An Essay on Landscape Painting, trans. Shio Sakanishi (London: John Murray, 1936), p. 36.

- In 2007, the Museum fur Gestaltung in Zurich mounted a fascinating exhibition entitled “From Inspiration to Innovation: Nature Design,” which examined new techniques for revealing nature and offered several interesting insights.

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Late Essays and Notes: Philosophy, Language, Culture, trans. Sergei Sandler (Resling

- Publishing, 2008), p. 39 (Hebrew; English translation, S.K.).

- Hélène Cixous, "The Laugh of the Medusa," trans. Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen, in Robyn R. Warhol and Diane Price Herndl (Eds.), Feminism: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism (New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1993), p. 338.

- Tretie Paleolog, Conversations with Brancusi, trans. Kenny Schuller (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 2004), p. 70 (Hebrew; English translation, S.K.)

69 Mazzeh Street

Tel Aviv 6578930, Israel

ayala@ayalaserfaty.com

+972 544 222 850

//

Maison Gerard Gallery

43 & 53 East 10th Street

New York, NY 10003

home@maisongerard.com

+1 212 674 7611

@ 2024 Ayala Serfaty, all rights reserved